Wall 1 – Early Hodinohso:ni’ history:

The elders were, and still are our most valued teachers. Learning has always been through oral tradition, the spoken word; hear it, learn it, live it. The woman shown in this image is a Clan Mother. She is the head matriarch of her extended clan family. Collectively, our Clan Mothers determine who our leaders will be, which is shown in the image of the Chief beside her.

The longhouse was the dwelling of the family. Many families lived within one longhouse. Agriculture was an essential way of life for the people, as demonstrated by the Three Sisters: corn, beans, and squash. The three sisters are sacred to the Hodinohso:ni’ because they originated from the time of creation.

Throughout the year, the Hodinohso:ni’ celebrate the different seasons, and all that is relevant to each season. These celebrations involve various ceremonies that are a way of giving thanks to all the elements of creation for the people's continued survival. The people perform many songs and dances with each ceremony. The music is provided by the Hodinohso:ni’ traditional drum and rattle. The Hodinohso:ni’ faithfully continue these cycles annually.

Wall 2 – Peace:

In a time of need when the Hodinohso:ni’ people were in turmoil, a man was trying to bring peace amongst his people. His name was Hayenwatha. He was instrumental in the creation of the first wampum ever to be used among the Hodinohso:ni’. As his idea for its use expanded, the Creator provided a more permanent medium for the wampum as shown with the hand bestowing the wampum beads. This led to a great confederation of the Hodinohso:ni’ Nations as expressed by the Great Law of Peace.

A noble man known as the Peace Maker, along with Hayenwatha, brought the Hodinohso:ni’ Nations together in peace. They formed a permanent unity of all the nations which fell under the title of “The Great Law of Peace.” The wampum called the Hayenwatha Belt represents the confederation that was established. The Circle wampum shown also represents that great confederation. It represents the leaders, 50 of them, who represent each nation within the great confederacy. It encapsulates all that is sacred and relevant to Hodinohso:ni’ culture.

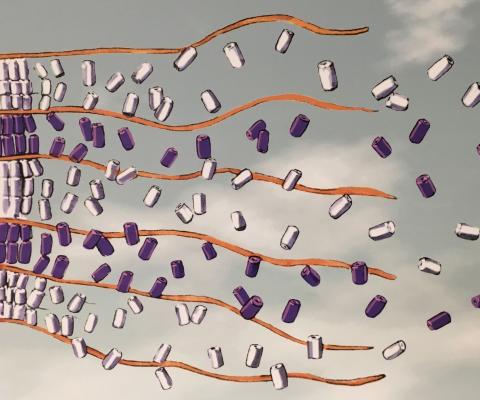

As time progressed the Hodinohso:ni’ witnessed the coming of the Europeans into their territory. It was then that wampum seemed to take on a different purpose. Dutch explorers formulated an agreement with the Hodinohso:ni’. A new wampum was created to represent their newly formed relationship called the Two Row belt. The Two Row belt proclaimed that both the Hodinohso:ni’ and the Dutch settlers shall sail down a river, side by side. The Ogwehoweh (original people) in their canoe, with their culture and beliefs, and the Dutch in their ship with their culture and beliefs. They shall travel side by side in peace, friendship, and respect, never interfering with each other's way of life. But as time went by that promise changed course. Through all of the years of council meetings and negotiations, pledging our commitments through wampum exchange, the truth began to reveal itself. That is revealed at the end of the Two Row wampum belt as it begins to fragment. The Ogwehoweh way of life was being torn apart, and they were cast into a new era of colonial dominance.

Wall 3 – Residential Schools:

In the early 1870s, measures were taken to eliminate native culture and language by means of a deliberate plan that was implemented by the government of Canada. Residential schools were set up to execute this plan and native youth, as seen by the line of children moving towards a residential school, were required to attend these schools. The expression on the young girl’s face bears witness to reveal just how devastating this experience was. The children seated in their desks became the norm for the cultural elimination process. As the artwork depicts, they have no faces. This attests to the fact that their identity was being erased through measures no child should have to endure.

Wall 4 – Resilience:

Although the residential school experience had a profound impact on Indigenous peoples, it failed in its attempt to completely eradicate the various ways of life. This is evident through many of the native community schools today that are implementing cultural teachings as well as language classes like the Bachelor of Arts in Ogwehoweh Languages here at Six Nations Polytechnic. The Ogwehoweh teachings are coming back, as shown by the young boy pointing to the chalkboard. Indigenous teachers have a strong presence in the schools today to help bring back all aspects of culture to the student body. That trend is gaining momentum across all First Nations in Canada and the United States. Many are attaining academic degrees and even as they attain those degrees, they are maintaining their cultural heritage. The true essence of the Two Row wampum has returned for the coming generations.

Modern education represents how far-reaching education is today for all First Nations people. Mother Earth is shown here and to demonstrate that while modern education may be present in our communities, we still adhere to the belief that we are all connected to the natural world. We are not separate from it, but part of it. It always has and will continue to provide for the people. Being only part of creation we must realize that we as humans are not the only living things upon the earth that deserve compassion and respect. All life is sacred.

Raymond R. Skye

Six Nations Iroquois Artist

2018